Naples' history phases

The origins

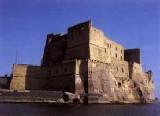

Naples’

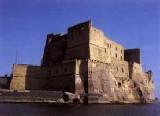

ancient origins can be found in a series of legends, among which the most

meaningful is the one about Partenope, a mermaid. Feeling shattered by Ulysses, who

succeded in escaping the mermaids’ enchanting song by his sheer cunning, she

committed suicide. Her body was found aground on

the rocks of a small island called Megaride, where nowadays you can see Castel

dell’Ovo. According to a less legendary version, Partenope was a marvellous young

woman, the daughter of a Greek commander,

Eumelo Falevo who had left for Campania to found a colony. Partenope died in a ship-wreck so her name was

given to the new-born town. As we know from historical sources, Greek colonies arrived on

the Isle of Ischia (IX century B.C.) and

later moved to Cuma; the city of Partenope

was founded on the Isle of Megaride in the 6th

century B.C. At that time Megaride was a commercial port trading with its

motherland; later on it expanded to Mount Echia (Pizzofalcone) and took the structure of a

small urban town.

Naples’

ancient origins can be found in a series of legends, among which the most

meaningful is the one about Partenope, a mermaid. Feeling shattered by Ulysses, who

succeded in escaping the mermaids’ enchanting song by his sheer cunning, she

committed suicide. Her body was found aground on

the rocks of a small island called Megaride, where nowadays you can see Castel

dell’Ovo. According to a less legendary version, Partenope was a marvellous young

woman, the daughter of a Greek commander,

Eumelo Falevo who had left for Campania to found a colony. Partenope died in a ship-wreck so her name was

given to the new-born town. As we know from historical sources, Greek colonies arrived on

the Isle of Ischia (IX century B.C.) and

later moved to Cuma; the city of Partenope

was founded on the Isle of Megaride in the 6th

century B.C. At that time Megaride was a commercial port trading with its

motherland; later on it expanded to Mount Echia (Pizzofalcone) and took the structure of a

small urban town.

Greek-Roman Naples

In 470 B.C. the Greek Cumaeans decided

to found a city and chose the eastest part of ancient Partenope, which is nowadays the

historical centre. They decided to call it "Neapolis" (new city) to be

distinguished from "Palepolis" (old city). At that time the city was probably an

aristocratic republic governed by two arcons and a council of nobles. From the point of

view of the urban structure, Neapolis was characterized by cards and decumans, according

to Greek tradition. The city was rich in religious and public buildings such as temples,

curia, theatres and hippodrome. It became an important Magna Grecia colony, together with

Taranto and Cuma. In the years to come, the Romans would be inspired by the culture, art

and traditions which enriched Neapolis in that period.

In 470 B.C. the Greek Cumaeans decided

to found a city and chose the eastest part of ancient Partenope, which is nowadays the

historical centre. They decided to call it "Neapolis" (new city) to be

distinguished from "Palepolis" (old city). At that time the city was probably an

aristocratic republic governed by two arcons and a council of nobles. From the point of

view of the urban structure, Neapolis was characterized by cards and decumans, according

to Greek tradition. The city was rich in religious and public buildings such as temples,

curia, theatres and hippodrome. It became an important Magna Grecia colony, together with

Taranto and Cuma. In the years to come, the Romans would be inspired by the culture, art

and traditions which enriched Neapolis in that period.

Although Neapolis was not a warlike city,

it had to defend itself from two notorious neighbours: the Samnites, who conquered Cuma in

423 B.C. and sent away its inhabitants, and the Romans, who were determined to expand

their dominiom in the south. At first the relationship between Rome and Neapolis was based on friendship and

commercial agreements but under the pressure of other colonies, Neapolis was forced not to

cooperate with the Romans any longer. In 326 B.C. the Roman Counsellor defeated the allied Samnites and Nola people. Peace

was not a dishonour since a confederation with Rome was created and Neapolis could keep

its istitutions and differencies. Years later Neapolis was a trusting ally of the more and

more powerful Romans. As a matter of fact

Neapolis was, to the Romans, an important means for Greek culture and civilization. Neapolis and

its surroundings became a privileged summer resort for Roman patricians, who built

luxurious villas between Puteoli and Sorrento. On

one hand Scipio the African, Silla, Tiberius, Caligola, Claudius, Nero, Brutus and

Lucullus chose these lands for simple relaxation and pleasure; on the other hand

Cicero, Horace, Pliny the Elder and Virgil found there inspiration to their artistic

genius. In other words Neapolis was a centre of sophisticated culture, a piece of Greece

in the Italian peninsula, always respected and admired by the Romans, who tried not to

oppress it or contaminate it.

Although Neapolis was not a warlike city,

it had to defend itself from two notorious neighbours: the Samnites, who conquered Cuma in

423 B.C. and sent away its inhabitants, and the Romans, who were determined to expand

their dominiom in the south. At first the relationship between Rome and Neapolis was based on friendship and

commercial agreements but under the pressure of other colonies, Neapolis was forced not to

cooperate with the Romans any longer. In 326 B.C. the Roman Counsellor defeated the allied Samnites and Nola people. Peace

was not a dishonour since a confederation with Rome was created and Neapolis could keep

its istitutions and differencies. Years later Neapolis was a trusting ally of the more and

more powerful Romans. As a matter of fact

Neapolis was, to the Romans, an important means for Greek culture and civilization. Neapolis and

its surroundings became a privileged summer resort for Roman patricians, who built

luxurious villas between Puteoli and Sorrento. On

one hand Scipio the African, Silla, Tiberius, Caligola, Claudius, Nero, Brutus and

Lucullus chose these lands for simple relaxation and pleasure; on the other hand

Cicero, Horace, Pliny the Elder and Virgil found there inspiration to their artistic

genius. In other words Neapolis was a centre of sophisticated culture, a piece of Greece

in the Italian peninsula, always respected and admired by the Romans, who tried not to

oppress it or contaminate it.

The Dukedom of Naples

In the early Middle Ages the history of Neapolis was

determined not only by the division of the Roman Empire but also by the invasion of

barbarian peoples and the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 A.D.). In 536 Justinian,

Emperor of the East, sent Belisario in order to conquer the city,  which

defended itself bravely. In 542 Naples was invaded by the Goths who definitely conquered

the Byzantine forces. Later on, the Byzantines reorganised themselves with Narsete and

took Naples once again as their dominion after a big battle at the foot of the volcano

Vesuvio, sending away the Goths from Campania. Under the undesired Byzantine domination,

Naples had to face the invasions of strong and uncivilized peoples i.e. the Vandals and

the Longobards. In 615 the attempt to gain independence brought about an independent

government which lasted for a short period of time. In 661 accepting a Neapolitan

petition, the Emperor of the East nominated Basilio, a Neapolitan duke, as head of the

city. In this way, even if it was still under Byzantium control, Naples had its own

government, which was at first nominated by the Byzantines, then elected before finally

becoming hereditary succession. Between 661 and 1137, after a period of difficult

struggle, Naples was one of the few oasis of civilization in the entire Italian peninsula,

surrounded by barbarian peoples

which

defended itself bravely. In 542 Naples was invaded by the Goths who definitely conquered

the Byzantine forces. Later on, the Byzantines reorganised themselves with Narsete and

took Naples once again as their dominion after a big battle at the foot of the volcano

Vesuvio, sending away the Goths from Campania. Under the undesired Byzantine domination,

Naples had to face the invasions of strong and uncivilized peoples i.e. the Vandals and

the Longobards. In 615 the attempt to gain independence brought about an independent

government which lasted for a short period of time. In 661 accepting a Neapolitan

petition, the Emperor of the East nominated Basilio, a Neapolitan duke, as head of the

city. In this way, even if it was still under Byzantium control, Naples had its own

government, which was at first nominated by the Byzantines, then elected before finally

becoming hereditary succession. Between 661 and 1137, after a period of difficult

struggle, Naples was one of the few oasis of civilization in the entire Italian peninsula,

surrounded by barbarian peoples

The Norman domination

During the

dukedom, Naples had to face the Longobards and the Saracens and sometimes asked for

mercenary help. Once called for help, the Normans were

given the feud of Aversa after withstanding Benevento

expansion. Under the Altavilla dynasty, however, the

Normans were no  longer satisfied with what

they had and started a series of campaigns; they defeated the Arabs, conquered Sicily

and wanted to expand in the

South of Italy. Roger II occupied Salerno, Capri, Amalfi and Ravello. In 1137 making an

greement with Duke Sergious, he imposed his power on Naples. At the duke’s death,

Roger granted independence and elected a

supervisor; then he set off for Palermo. In

1154 William, known as Il Malo, succeeded Roger at his death. Despite his name – which

means “The Naughty”, “The Evil” – he was a wise and good king who

ordered the construction of Castel Capuano, contracted

alliances with the Maritime Republics and enjoyed Neapolitan aristocrats’ respect.

During his reign the history of Naples was closely tied to the history of Palermo. William

II, known as “Il Buono” –“The Good” – succeeded and ruled

wisely. At his death, in order not to let the reign fall into the hands of the Germans who

were pressing the bounderies, Tancredi d’Altavilla was called as his successor by an

assembly of nobles, prelates and representatives of the people. The Norman domination was

about to disappear since, after contrasting the Suevian siege in 1191, at Tancredi’s

death in 1194, the German sovereign Henry VI conquered the South of Italy.

longer satisfied with what

they had and started a series of campaigns; they defeated the Arabs, conquered Sicily

and wanted to expand in the

South of Italy. Roger II occupied Salerno, Capri, Amalfi and Ravello. In 1137 making an

greement with Duke Sergious, he imposed his power on Naples. At the duke’s death,

Roger granted independence and elected a

supervisor; then he set off for Palermo. In

1154 William, known as Il Malo, succeeded Roger at his death. Despite his name – which

means “The Naughty”, “The Evil” – he was a wise and good king who

ordered the construction of Castel Capuano, contracted

alliances with the Maritime Republics and enjoyed Neapolitan aristocrats’ respect.

During his reign the history of Naples was closely tied to the history of Palermo. William

II, known as “Il Buono” –“The Good” – succeeded and ruled

wisely. At his death, in order not to let the reign fall into the hands of the Germans who

were pressing the bounderies, Tancredi d’Altavilla was called as his successor by an

assembly of nobles, prelates and representatives of the people. The Norman domination was

about to disappear since, after contrasting the Suevian siege in 1191, at Tancredi’s

death in 1194, the German sovereign Henry VI conquered the South of Italy.

Naples under the Suevian

dominion

Henry

VI ruled Naples for three years which were not so happy for the city itself. He was

succeeded by Frederick II who is nowadays

considered one of the greatest sovereign ever ascended a

European throne. At first his relationship with the city was not easy; as a matter of fact

several attempts to subvert his reign were planned. But things improved and when he

visited the city in 1220 first and then in

1222, he was positively impressed and

promoted many works of embellishment and

restoration. He was a man of great culture who created

a strong centrally-organized power, rearranged

public administration, justice, trade and army. Not only did he successfully

impose himself in many military campaigns in Germany and Jerusalem, but he also promoted

culture and art, being surrounded by poets, philosophers and scholars.

Henry

VI ruled Naples for three years which were not so happy for the city itself. He was

succeeded by Frederick II who is nowadays

considered one of the greatest sovereign ever ascended a

European throne. At first his relationship with the city was not easy; as a matter of fact

several attempts to subvert his reign were planned. But things improved and when he

visited the city in 1220 first and then in

1222, he was positively impressed and

promoted many works of embellishment and

restoration. He was a man of great culture who created

a strong centrally-organized power, rearranged

public administration, justice, trade and army. Not only did he successfully

impose himself in many military campaigns in Germany and Jerusalem, but he also promoted

culture and art, being surrounded by poets, philosophers and scholars.

Angevin Naples

In

1266 the Pope himself asked Carlo d’Angiò, the brother of the king of France, to

come to Italy. He arrived, defeated Manfredi

in Benevento and became king of the South of Italy.The city became the capital of the

reign, despite strong protests from Sicily. Neapolitain society was rearranged in  what were called Sedili, democratic intermediary organisms between

the sovereign and the people. Strong tax regulations didin’t prevent Naples from

developing into a city rich in marvellous churches, dignified factories and expanding craftmanship and trade. In this period

population increased enormously so that Naples became the first city in Italy and the

second in Europe after Paris. Nevertheless, the king had hard times to come when, in 1267,

he had to face a new attack from Corradino, who was beheaded in the bloom of youth in

Piazza Mercato after being defeated inTagliacozzo. In 1282 the Sicilian Vespers brought

about the loss of Sicily and two years later an

uprising supported by the guibellines was soffocated with the help of the local

aristocracy. At Carlo’s death in 1285, Carlo II came to the throne. He proved

to be a good legislator and improved

the artistic city wealth – we owe him the enlargement of the city walls, the

restructuring of Castel dell’Ovo and the

restyling of Maschio Angioino, built by his father. In 1309 another great king ascended

the throne of Naples:

what were called Sedili, democratic intermediary organisms between

the sovereign and the people. Strong tax regulations didin’t prevent Naples from

developing into a city rich in marvellous churches, dignified factories and expanding craftmanship and trade. In this period

population increased enormously so that Naples became the first city in Italy and the

second in Europe after Paris. Nevertheless, the king had hard times to come when, in 1267,

he had to face a new attack from Corradino, who was beheaded in the bloom of youth in

Piazza Mercato after being defeated inTagliacozzo. In 1282 the Sicilian Vespers brought

about the loss of Sicily and two years later an

uprising supported by the guibellines was soffocated with the help of the local

aristocracy. At Carlo’s death in 1285, Carlo II came to the throne. He proved

to be a good legislator and improved

the artistic city wealth – we owe him the enlargement of the city walls, the

restructuring of Castel dell’Ovo and the

restyling of Maschio Angioino, built by his father. In 1309 another great king ascended

the throne of Naples:  his name was

Roberto d’Angiò, known as the Wise, a

man of art and culture who was able to create a remarkable intellectual climate.

Boccaccio, Giotto, Petrarca and Tino da Camaino lived and worked in Naples at that time.

Roberto D’Angiò promoted legislative studies, ordered the construction of the Church

of S. Chiara – where we can find his funeral monument – and witnessed the

flourish of gothic style – churches of S. Lorenzo, S.

Paolo Maggiore, San Domenico Maggiore, Incoronata. At

his death in 1343 his niece Giovanna found herself in a series of terrible events - riots,

plague and Hungarian invasions - which

affected the city. She also caused some trouble with her frivolous and senseless

behaviour. After forty years of rule her nephew Carlo Durazzo d’Angiò, who was

considered very reliable and trustful by the

queen herself, murdered her and took the

throne. He died a few years later and the Durazzo family, a secondary descent of the

d’Angiòs, brought young Ladislao onto

the throne of Naples. Luigi II d’Angiò was very hostile to him since he claimed the

throne for himself. Despite the city division

into two factions, Ladislao succeded in taking control and ruled as a good king. In 1404

he conquered Rome in order to unify the peninsula but he had to abandon it in 1409. He

died at the age of forty and left the throne to his sister Giovanna who, like her ancestor

with the same name, was devoted to love affairs and scandals more than to queen’s

activities.

his name was

Roberto d’Angiò, known as the Wise, a

man of art and culture who was able to create a remarkable intellectual climate.

Boccaccio, Giotto, Petrarca and Tino da Camaino lived and worked in Naples at that time.

Roberto D’Angiò promoted legislative studies, ordered the construction of the Church

of S. Chiara – where we can find his funeral monument – and witnessed the

flourish of gothic style – churches of S. Lorenzo, S.

Paolo Maggiore, San Domenico Maggiore, Incoronata. At

his death in 1343 his niece Giovanna found herself in a series of terrible events - riots,

plague and Hungarian invasions - which

affected the city. She also caused some trouble with her frivolous and senseless

behaviour. After forty years of rule her nephew Carlo Durazzo d’Angiò, who was

considered very reliable and trustful by the

queen herself, murdered her and took the

throne. He died a few years later and the Durazzo family, a secondary descent of the

d’Angiòs, brought young Ladislao onto

the throne of Naples. Luigi II d’Angiò was very hostile to him since he claimed the

throne for himself. Despite the city division

into two factions, Ladislao succeded in taking control and ruled as a good king. In 1404

he conquered Rome in order to unify the peninsula but he had to abandon it in 1409. He

died at the age of forty and left the throne to his sister Giovanna who, like her ancestor

with the same name, was devoted to love affairs and scandals more than to queen’s

activities.

Naples under the

Aragoneses

A few years before dying, Giovanna Durazzo called for the

help of Alfonso d'Aragona, king of Sicily. He adopted her, this way justifying his right

to  succession to the throne. Finally she changed her mind

and nominated Renato d'Angiò as her heir; as a consequence, the Aragonese sovereign felt

betrayed, put Naples under siege and conquered it in 1442. This was the beginning of the

Aragonese dominion which paved the way for a civil and economic development of the city

and the florishing of Renaissance art and ideals: artists such as Giovanni Pontano, Jacopo

Sannazaro, Pietro Summonte, Pietro Beccadelli and Lorenzo Valli could demonstrate their

talents thanks to the stimulating atmosphere created by Alfonso, who deserved the name of

Magnanimo (generous, high-minded). Grand monuments still remain as evidence of that

grandeur: the marble arch of Castel Nuovo - which the sovereign wanted so as to celebrate

the conquest of the city - , the church of S. Anna del Lombardi, the church of S. Angelo

al Nilo, great works which saw the contribution of Vasari and Donatello. In 1458 at

Alfonso's death the crown of Naples passed to his son Ferrante while Giovanni, another of

his sons, was given the crown of Sicily. Under Ferrante's reign, Naples

succession to the throne. Finally she changed her mind

and nominated Renato d'Angiò as her heir; as a consequence, the Aragonese sovereign felt

betrayed, put Naples under siege and conquered it in 1442. This was the beginning of the

Aragonese dominion which paved the way for a civil and economic development of the city

and the florishing of Renaissance art and ideals: artists such as Giovanni Pontano, Jacopo

Sannazaro, Pietro Summonte, Pietro Beccadelli and Lorenzo Valli could demonstrate their

talents thanks to the stimulating atmosphere created by Alfonso, who deserved the name of

Magnanimo (generous, high-minded). Grand monuments still remain as evidence of that

grandeur: the marble arch of Castel Nuovo - which the sovereign wanted so as to celebrate

the conquest of the city - , the church of S. Anna del Lombardi, the church of S. Angelo

al Nilo, great works which saw the contribution of Vasari and Donatello. In 1458 at

Alfonso's death the crown of Naples passed to his son Ferrante while Giovanni, another of

his sons, was given the crown of Sicily. Under Ferrante's reign, Naples  had to defend itself from Angevin claims - who were won at Sarno and in

Ischia during a naval battle - and from Florence in 1458. Several times the barons

conspired against Ferrante, despite the fact that he was a good king and a fine

legislator. During his reign the majestic Porta Capuana was built. When Ferrante died in

1493, Alfonso II ascended the throne but he soon abdicated in favour of his son,

Ferrantino, under the pressure of a likely French throne claim. In fact, Ferrantino wasn't

able to oppose Carlo VIII French army long and escaped to Ischia while the Angevins were

entering Naples. Only when Carlo went back to Paris and left behind few garrisons was he

able to enter the city again supported by the Neapolitan people. He died two years later,

mourned by the people. The crown passed to his uncle Frederick d'Altamura

had to defend itself from Angevin claims - who were won at Sarno and in

Ischia during a naval battle - and from Florence in 1458. Several times the barons

conspired against Ferrante, despite the fact that he was a good king and a fine

legislator. During his reign the majestic Porta Capuana was built. When Ferrante died in

1493, Alfonso II ascended the throne but he soon abdicated in favour of his son,

Ferrantino, under the pressure of a likely French throne claim. In fact, Ferrantino wasn't

able to oppose Carlo VIII French army long and escaped to Ischia while the Angevins were

entering Naples. Only when Carlo went back to Paris and left behind few garrisons was he

able to enter the city again supported by the Neapolitan people. He died two years later,

mourned by the people. The crown passed to his uncle Frederick d'Altamura

The Spanish

viceroyalty

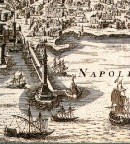

With

the definition “Spanish viceroyalty” we refer to a period of almost two

centuries of colonialistic domination. Between 1503 and 1707 the crown of Madrid exerted

its power on Naples and the whole reign with eagerness as well as inability.  A host of viceroys took regency of the city

and proved to be devoted to vexations; they also stole works of art and imposed heavy

taxes. In this period in order to defend and

support the people from Spanish arrogance, a kind of secret society, called

“camorra”, was arranged; at first its aim was to offer mutual assistance. Lots

of insurrections and warlike events took place in those years: Venice’s possessions

in Puglia were occupied, the African expeditions to Tunisi and Tripoli –and the

victory in Lepanto- were carried out, the French invasion was pushed back in 1526 and

several Arab and Turkish pirate raids were faced. At home there were lots of uprisings due

to heavy taxes and attempts to introduce the

Inquisition. The most famous and daring one was in 1647 when Masaniello, the head of a

group of fierce people, hold the Spanish

A host of viceroys took regency of the city

and proved to be devoted to vexations; they also stole works of art and imposed heavy

taxes. In this period in order to defend and

support the people from Spanish arrogance, a kind of secret society, called

“camorra”, was arranged; at first its aim was to offer mutual assistance. Lots

of insurrections and warlike events took place in those years: Venice’s possessions

in Puglia were occupied, the African expeditions to Tunisi and Tripoli –and the

victory in Lepanto- were carried out, the French invasion was pushed back in 1526 and

several Arab and Turkish pirate raids were faced. At home there were lots of uprisings due

to heavy taxes and attempts to introduce the

Inquisition. The most famous and daring one was in 1647 when Masaniello, the head of a

group of fierce people, hold the Spanish  “masters”

in check for more than a year. They were finally defeated after the taking of their

headquarter in Castello del armine. From an artistic point of view, the city saw a group of great men of arts and

culture working and expressing their

talents: Tasso, Giovambattista Basile and Giambattista Marino in literature; Tommaso

Campanella, Giordano Bruno and Giambattista Vico in philosophy; Massimo Stanzione,

Battistello Caracciolo, Bernardo Cavallino, Salvator Rosa, Luca Giordano, Mattia Preti and

Andrea da Salerno in painting; Pietro Bernini, Michelangelo Naccherino, Giovanni da Nola

and Girolamo Santacroce in sculpure; Domenico Fontana and Cosimo Fanzago in architecture;

among some of the most important works we can still admire the Royal Palace, San Martino Certosa and the Church of Gesù

Nuovo.uovo.

“masters”

in check for more than a year. They were finally defeated after the taking of their

headquarter in Castello del armine. From an artistic point of view, the city saw a group of great men of arts and

culture working and expressing their

talents: Tasso, Giovambattista Basile and Giambattista Marino in literature; Tommaso

Campanella, Giordano Bruno and Giambattista Vico in philosophy; Massimo Stanzione,

Battistello Caracciolo, Bernardo Cavallino, Salvator Rosa, Luca Giordano, Mattia Preti and

Andrea da Salerno in painting; Pietro Bernini, Michelangelo Naccherino, Giovanni da Nola

and Girolamo Santacroce in sculpure; Domenico Fontana and Cosimo Fanzago in architecture;

among some of the most important works we can still admire the Royal Palace, San Martino Certosa and the Church of Gesù

Nuovo.uovo.

The Borbons

The French decade

The Borbons' return

Naples after

Unification

Contemporary Naples

Back to Home Page

Naples’

ancient origins can be found in a series of legends, among which the most

meaningful is the one about Partenope, a mermaid. Feeling shattered by Ulysses, who

succeded in escaping the mermaids’ enchanting song by his sheer cunning, she

committed suicide. Her body was found aground on

the rocks of a small island called Megaride, where nowadays you can see Castel

dell’Ovo. According to a less legendary version, Partenope was a marvellous young

woman, the daughter of a Greek commander,

Eumelo Falevo who had left for Campania to found a colony. Partenope died in a ship-wreck so her name was

given to the new-born town. As we know from historical sources, Greek colonies arrived on

the Isle of Ischia (IX century B.C.) and

later moved to Cuma; the city of Partenope

was founded on the Isle of Megaride in the 6th

century B.C. At that time Megaride was a commercial port trading with its

motherland; later on it expanded to Mount Echia (Pizzofalcone) and took the structure of a

small urban town.

Naples’

ancient origins can be found in a series of legends, among which the most

meaningful is the one about Partenope, a mermaid. Feeling shattered by Ulysses, who

succeded in escaping the mermaids’ enchanting song by his sheer cunning, she

committed suicide. Her body was found aground on

the rocks of a small island called Megaride, where nowadays you can see Castel

dell’Ovo. According to a less legendary version, Partenope was a marvellous young

woman, the daughter of a Greek commander,

Eumelo Falevo who had left for Campania to found a colony. Partenope died in a ship-wreck so her name was

given to the new-born town. As we know from historical sources, Greek colonies arrived on

the Isle of Ischia (IX century B.C.) and

later moved to Cuma; the city of Partenope

was founded on the Isle of Megaride in the 6th

century B.C. At that time Megaride was a commercial port trading with its

motherland; later on it expanded to Mount Echia (Pizzofalcone) and took the structure of a

small urban town.  In 470 B.C. the Greek Cumaeans decided

to found a city and chose the eastest part of ancient Partenope, which is nowadays the

historical centre. They decided to call it "Neapolis" (new city) to be

distinguished from "Palepolis" (old city). At that time the city was probably an

aristocratic republic governed by two arcons and a council of nobles. From the point of

view of the urban structure, Neapolis was characterized by cards and decumans, according

to Greek tradition. The city was rich in religious and public buildings such as temples,

curia, theatres and hippodrome. It became an important Magna Grecia colony, together with

Taranto and Cuma. In the years to come, the Romans would be inspired by the culture, art

and traditions which enriched Neapolis in that period.

In 470 B.C. the Greek Cumaeans decided

to found a city and chose the eastest part of ancient Partenope, which is nowadays the

historical centre. They decided to call it "Neapolis" (new city) to be

distinguished from "Palepolis" (old city). At that time the city was probably an

aristocratic republic governed by two arcons and a council of nobles. From the point of

view of the urban structure, Neapolis was characterized by cards and decumans, according

to Greek tradition. The city was rich in religious and public buildings such as temples,

curia, theatres and hippodrome. It became an important Magna Grecia colony, together with

Taranto and Cuma. In the years to come, the Romans would be inspired by the culture, art

and traditions which enriched Neapolis in that period.

which

defended itself bravely. In 542 Naples was invaded by the Goths who definitely conquered

the Byzantine forces. Later on, the Byzantines reorganised themselves with Narsete and

took Naples once again as their dominion after a big battle at the foot of the volcano

Vesuvio, sending away the Goths from Campania. Under the undesired Byzantine domination,

Naples had to face the invasions of strong and uncivilized peoples i.e. the Vandals and

the Longobards. In 615 the attempt to gain independence brought about an independent

government which lasted for a short period of time. In 661 accepting a Neapolitan

petition, the Emperor of the East nominated Basilio, a Neapolitan duke, as head of the

city. In this way, even if it was still under Byzantium control, Naples had its own

government, which was at first nominated by the Byzantines, then elected before finally

becoming hereditary succession. Between 661 and 1137, after a period of difficult

struggle, Naples was one of the few oasis of civilization in the entire Italian peninsula,

surrounded by barbarian peoples

which

defended itself bravely. In 542 Naples was invaded by the Goths who definitely conquered

the Byzantine forces. Later on, the Byzantines reorganised themselves with Narsete and

took Naples once again as their dominion after a big battle at the foot of the volcano

Vesuvio, sending away the Goths from Campania. Under the undesired Byzantine domination,

Naples had to face the invasions of strong and uncivilized peoples i.e. the Vandals and

the Longobards. In 615 the attempt to gain independence brought about an independent

government which lasted for a short period of time. In 661 accepting a Neapolitan

petition, the Emperor of the East nominated Basilio, a Neapolitan duke, as head of the

city. In this way, even if it was still under Byzantium control, Naples had its own

government, which was at first nominated by the Byzantines, then elected before finally

becoming hereditary succession. Between 661 and 1137, after a period of difficult

struggle, Naples was one of the few oasis of civilization in the entire Italian peninsula,

surrounded by barbarian peoples

succession to the throne. Finally she changed her mind

and nominated Renato d'Angiò as her heir; as a consequence, the Aragonese sovereign felt

betrayed, put Naples under siege and conquered it in 1442. This was the beginning of the

Aragonese dominion which paved the way for a civil and economic development of the city

and the florishing of Renaissance art and ideals: artists such as Giovanni Pontano, Jacopo

Sannazaro, Pietro Summonte, Pietro Beccadelli and Lorenzo Valli could demonstrate their

talents thanks to the stimulating atmosphere created by Alfonso, who deserved the name of

Magnanimo (generous, high-minded). Grand monuments still remain as evidence of that

grandeur: the marble arch of Castel Nuovo - which the sovereign wanted so as to celebrate

the conquest of the city - , the church of S. Anna del Lombardi, the church of S. Angelo

al Nilo, great works which saw the contribution of Vasari and Donatello. In 1458 at

Alfonso's death the crown of Naples passed to his son Ferrante while Giovanni, another of

his sons, was given the crown of Sicily. Under Ferrante's reign, Naples

succession to the throne. Finally she changed her mind

and nominated Renato d'Angiò as her heir; as a consequence, the Aragonese sovereign felt

betrayed, put Naples under siege and conquered it in 1442. This was the beginning of the

Aragonese dominion which paved the way for a civil and economic development of the city

and the florishing of Renaissance art and ideals: artists such as Giovanni Pontano, Jacopo

Sannazaro, Pietro Summonte, Pietro Beccadelli and Lorenzo Valli could demonstrate their

talents thanks to the stimulating atmosphere created by Alfonso, who deserved the name of

Magnanimo (generous, high-minded). Grand monuments still remain as evidence of that

grandeur: the marble arch of Castel Nuovo - which the sovereign wanted so as to celebrate

the conquest of the city - , the church of S. Anna del Lombardi, the church of S. Angelo

al Nilo, great works which saw the contribution of Vasari and Donatello. In 1458 at

Alfonso's death the crown of Naples passed to his son Ferrante while Giovanni, another of

his sons, was given the crown of Sicily. Under Ferrante's reign, Naples  had to defend itself from Angevin claims - who were won at Sarno and in

Ischia during a naval battle - and from Florence in 1458. Several times the barons

conspired against Ferrante, despite the fact that he was a good king and a fine

legislator. During his reign the majestic Porta Capuana was built. When Ferrante died in

1493, Alfonso II ascended the throne but he soon abdicated in favour of his son,

Ferrantino, under the pressure of a likely French throne claim. In fact, Ferrantino wasn't

able to oppose Carlo VIII French army long and escaped to Ischia while the Angevins were

entering Naples. Only when Carlo went back to Paris and left behind few garrisons was he

able to enter the city again supported by the Neapolitan people. He died two years later,

mourned by the people. The crown passed to his uncle Frederick d'Altamura

had to defend itself from Angevin claims - who were won at Sarno and in

Ischia during a naval battle - and from Florence in 1458. Several times the barons

conspired against Ferrante, despite the fact that he was a good king and a fine

legislator. During his reign the majestic Porta Capuana was built. When Ferrante died in

1493, Alfonso II ascended the throne but he soon abdicated in favour of his son,

Ferrantino, under the pressure of a likely French throne claim. In fact, Ferrantino wasn't

able to oppose Carlo VIII French army long and escaped to Ischia while the Angevins were

entering Naples. Only when Carlo went back to Paris and left behind few garrisons was he

able to enter the city again supported by the Neapolitan people. He died two years later,

mourned by the people. The crown passed to his uncle Frederick d'Altamura